It was a tense evening at the meeting of the executive council of the Minnesota Historical Society on November 11, 1901. An invited speaker had given a speech for the ostensible purpose of telling the ancient history of the state, but at the end of his speech had condemned the white settlers and the U.S. government for its treatment of Minnesota’s Native inhabitants and had prophesied disaster for the whites of Minnesota if they did not renounce such actions.

Despite these plain words, the speaker went home that night thinking that he had been too polite; he had failed to tell the whole truth. Writing in his diary he stated: “Several members of the Historical Society are related in various ways to the gigantic robberies which have been perpetrated against the Indians in the Northwest. Henry M. Rice and Henry H. Sibley, deceased, were extensively involved in shaping the policy of the government against Minnesota Indian tribes.” He had withheld these facts from his speech, giving only a mild and general condemnation of the treatment of Indian people, but had still received a negative response. As a result, he wrote, “I now pledge myself never again to suppress facts in history to satisfy the desires of thieves.”

While many in the audience that evening enjoyed the first part of the talk, others believed that the speaker had been too radical. The president of the society thanked the speaker for his remarks but asked him to revise and reconsider them before submitting them in writing to the society, which the speaker refused to do. At that point the society held its business meeting at which a number of wealthy and influential Minnesotans were voted life memberships in the institution.

The events of that evening in 1901 represent well the position of the Minnesota Historical Society in relation to controversial aspects of the state’s history. The role of the historical society in recording and recounting such events has often been contested. Though the institution is not a state agency, it has quasi-official status, one that it nurtures for its own perpetuation. As a result, the institution, whether it wants to or not, is viewed as presenting an official version of history, if not the whole truth. The problematic nature of the historical society’s precarious role is most evident when it comes to those topics perceived as “unpleasant,” where the truth does not cast a happy glow on the leaders of the state.

Given the polite nature of the 1901 newspaper articles which record the events it is hard to know how tense things were in the room that evening. However, based on the bare description of what happened, it is impossible to imagine such an evening occurring at a meeting of the executive council of the Minnesota Historical Society in the year 2011. Today the executive council is still a body composed of the rich and influential. And at least in the last twenty years during the tenure of the recently ex-director, annual meetings are routine, formalistic affairs with catered food, run with the precision of a Politburo gathering or a show trial. Controversy is never let in the door and if it gets in it is escorted out.

It may be that if the Minnesota Historical Society is ever to confront the controversies in Minnesota’s history, it will first have to confront the nature of its own organization as one begun to serve the interests of wealthy and influential whites, who sought to preserve history to celebrate and perpetuate their own points of view. In doing so the society must remember events such as the one in November 1901, when controversy came in the door and spoke.

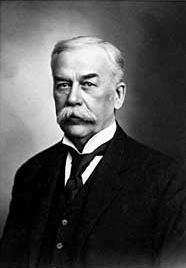

It is important to know that the speaker that evening was Jacob V. Brower, a former legislator, an archaeologist, and a conservationist known for having fought for the creation in 1891 of Minnesota’s first state park, Itasca State Park. Brower was a friend of the historical society. Even after what occurred that night in 1901, Brower, with the help of his son, the legislator Ripley Brower, helped the society get a large appropriation from the state legislature. He saw plainly that while the institution of the society was flawed, the preservation of history was vital. But Brower was not a saint; he could be intemperate in the expression of his opinions; he sometimes dug into burial mounds. But his consistency in his view of history was admirable, especially in a time when corruption in government and business was often overlooked in writing history.

Brower had an unflagging interest in the burial mounds and other earthworks through which the ancient inhabitants of Minnesota had left their mark on the landscape of their homelands. But unlike others with an interest in such earthworks, Brower was convinced that these were placed where they were by the ancestors of the Dakota, not by some ancient people who later disappeared.

Having made that connection between ancient history and the contemporary world, Brower overcame the compartmentalization that plagues many historians and archaeologists. He could not and would not ignore the treatment accorded Minnesota’s Native people in the 19th century by colonization, settlement, and exile. And having taken that step Brower could not ignore that the Minnesota Historical Society and its rich and influential members were bound up inextricably in that very process.

In many ways November 11, 1901 was the last straw for Jacob Brower. He had just published, at his own expense, a book called Kathio, which recorded the history of Mille Lacs Lake, an ancient homeland of the Dakota people. While researching and writing the book, Brower had become aware of the treatment of the Mille Lacs Ojibwe, whose pinelands and reservation lands were in the process of being stolen by timber companies. Scandalized by what was occurring and the involvement of wealthy and influential Minnesotans, he began to view the history of the state in a different manner, connecting the events of 1900 at Mille Lacs with what had happened to the Dakota in 1862. Not all of these insights had been included in Kathio, but as a result of what occurred on the evening of November 11, 1901, Brower decided that he would no longer refrain from telling the truth, regardless of the consequences.

It is clear that Brower had not originally intended to speak plainly about the corruption in the treatment of the Native people in Minnesota. His remarks at the end of his speech were probably an afterthought, the expression of ideas that had been percolating with increasing intensity in his mind. At the same time those who came to the speech appear not to have expected what he said. Not used to hearing radical opinions, members of the historical society, who were joined that evening by many invited guests, had gathered to hear a “highly interesting and instructive paper on the earliest known history of the state of Minnesota.”

But the audience did not include just the rich and influential members of the society. Also present were two Indian leaders, Nishotah or the minister Charles T. Wright of the White Earth Reservation and Mozomoni, a leader on the Mille Lacs Reservation. They were both friends of Brower’s, men he had gotten to know while doing his research. Both men came from reservations under assault by timber companies allied with the most influential leaders in the state. With these leaders in the audience, along with members of the Historical Society who themselves or whose families were complicit in frauds against Indian people, how could Brower do anything else but tell the truth about what was happening?

Several St. Paul newspapers reported the events of the evening. The St. Paul Globe noted on November 12, 1901, under the headline “BROWER IS SEVERE,” that the audience seemed to enjoy the talk, but that some members recoiled at the remarks at the end. After speaking of the ancient settlement of the Dakotas, “the author condemned the white settlers and United States government in most severe terms for their treatment of the Indians, and in closing, prophesied that if the present policies were pursued some writers would some day not far distant be called upon to chronicle the downfall of the government because it had been so mercenary.”

Various members of the audience were upset that Brower, “in his sympathy for the Indians, had been led to too severe arraignment of the white settlers.” General John B. Sanborn, president of the historical society, objected to the tone Brower had taken. The Globe reported Sanborn stating that he was “somewhat inclined to consider that Mr. Brower had been too radical in some of his expressions.” Sanborn moved a vote of thanks to Brower “suggesting that the author of the paper be requested to reconsider and possibly modify some of his remarks before the paper was made a record of the society.” Brower responded stating that his paper had been prepared at his own expense and was not a record of the society and that therefore he would not amend it. And then the Society moved on to its business meeting during which a number of wealthy and influential individuals were elected to life membership in the organization.

Sanborn did not get the last word. Brower’s books are now a valued part of the Minnesota Historical Society’s collections. Even more important are his journals, where one can read today Brower’s own eloquent words about the events of that evening in 1901. These words continue to have great relevance today.

Jacob V. Brower journal, November 11, 1901.

I tonight delivered “Kathio” as an address before the Minnesota Historical Society. I regret exceedingly that many historic facts were suppressed from that book, but several members of the Historical Society are related in various ways to the gigantic robberies which have been perpetrated against the Indians in the Northwest. Henry M. Rice and Henry H. Sibley, deceased, were extensively involved in shaping the policy of the government against Minnesota Indian tribes. The great Sioux outbreak of 1862 was precipitated as a result of the operations of thieves among all the bands who wore official garbs and spoke by authority; they acted nominally for the Government but principally for themselves. As a resume of the causes which precipitated the Sioux Outbreak of 1862 would be distasteful to the Minnesota Historical Society of that event in “Kathio.”

Even with all those and many other facts suppressed the Society received coldly and with indifference the few references I have made to the manner in which the Indians have been cheated, wronged, and defrauded by the people of the United States.

Even the gigantic fraud perpetrated by Dwight M. Sabin, a United States Senator, against the Mille Lac Indians at Kathio, remains unmentioned by me today. But I now pledge myself never again to suppress facts in history to satisfy the desires of thieves. Sabin stole all the Indian pine at Mille Lac and W. D. Washburn was a party to the secret arrangement, but finally got left by Sabin’s sharp trickery.

All that is left out of “Kathio” Henry M. Rice went to Mille Lac and uttered gross deceptions to the Ojibway people and by fraud secured their signatures to the convention of October 5th, 1889, and today those poor people as a consequence are starving and in abject want, 963 of them.

All that history lays on my table–suppressed from “Kathio.” I curse such proceedings and I am ashamed of my own book which suppresses the facts to satisfy the demands of a society which stands ready to approve the manner of undoing the Indian tribes.

The John B. Sanborn who objected to my reference to the manner of cheating the Indians, is the same John B. Sanborn who married a niece of Henry M. Rice–and also–charged the Sisseton band a fee of $50,000.00 for services as an attorny; at least so reported, and I suppressed that fact. He collect[ed] the fee by Act of Congress.

Nothwithstanding all these suppresed facts the members of the Minnesota Historical Society turn a deaf ear to my appeal for justice to the Indian[s] of Kathio.

December 9, 1901

[An account prompted by another meeting of the executive council of the historical society in which several speakers, including General John B. Sanborn, were to speak on Indian history in Minnesota.]

The secretary [Warren Upham] and other members of the Minnesota Historical Society have gotten up an attempted demonstration against my statement of facts contained in my printed address delivered to the Society Nov. 11, 1901, entitled Kathio. They will find it hard to suppress or circumvent, or obliterate questions of historical fact contained in a printed book. The meeting to justify all acts against the Indians was a complete failure. Neither of the speakers announced were present at the meeting. A short paper written by Judge Flandrau was read. He cracked a few jokes and described a few old Indians and wound up by saying that the Indian had been as well treated as he in any way deserved. Flandrau was one of the men who contributed to the causes which brought on the Sioux Outbreak of 1862.