Minnesota has a history, and that not altogether an unwritten one, which can unravel many a page of deep, engrossing interest–Alexander Ramsey on becoming the chair of the Minnesota Historical Society in 1851

History is the lifeblood of communities. There is no community without history and the free and open access to that history marks the difference between liberty and tyranny. People who keep history–whether elders, storytellers, archivists, librarians, or even professional historians–who gather it and pass it on to others, perform a crucial function in any society. If history is not kept or if it is kept but not passed on or if it is kept and passed on in distorted or untruthful ways, then the soul of the community where this occurs will suffer.

My intention is to praise the Historical Society not to defend it. The Historical Society has been criticized for its role in supporting a master narrative or dominant form of history, one that is harmful to Native people, particularly the Dakota of Minnesota who were exiled from this state in 1862 and whose struggle to restore their place here has been long and continuing. I agree with this criticism, although I believe this is not done wittingly, or with a full understanding. Not that this makes the result any more defensible. But before discussing that point, I need to state my own admiration and support for the very real contribution made by the Historical Society–its mission, its collections, its wonderful staff, and its future. The Historical Society’s role in the state provides, in fact, the very means for attacking the master narrative and providing an alternative history which acknowledges the role of Native people in Minnesota and documents the genocide committed upon them. (Of course, I do have numerous conflicts of interest involving the Historical Society, as discussed below.)

The Minnesota Historical Society, through its library, its archives, and its museum collections is Minnesota’s history-keeper. From the Society’s very beginnings it has gathered the records of this place and this state, in manuscripts, books, newspapers, photographs, oral histories, information, and objects. And it has preserved and disseminated the information assembled in endless and useful ways. In this it has performed a crucial cultural role, one that helps to make Minnesota a better place. Whenever this cultural role is harmed or diminished, whenever the budget of these programs is cut, Minnesota itself is diminished.

Archives, libraries, collections, and the gathering of diverse sources of information are a key function of any society. Without such institutions a people cannot exist as a people. Societies without written records still have historians who help others to see where they came from and where they are going. Oral histories, legends, winter counts on buffalo skin are as important a record as the collected records of a state legislature.

Of course, even totalitarian and criminal societies keep records, often very meticulous ones. The Nazis kept gruesome records of their worst acts. Organized crime keeps careful financial records. In terms of record-keeping one difference between such societies and free and open societies is the degree to which the records are open, accessible, and freely disseminated. Open records are a key to accountability. If a society makes no provision for such access and dissemination and does not support it with adequate funding this causes great harm to democracy.

The Minnesota Historical Society has not always been the State Archives, but its tradition of record-keeping goes back to its beginnings. It is no accident that the second Archivist of the United States, Solon J. Buck, was for many years the director of the Minnesota Historical Society. Some will note that the origin of the Historical Society is enmeshed in the very processes through which criminal acts were committed by the Territory and State of Minnesota against Native people. The first records collected by the Historical Society of Indian people were designed to document a “dying race.” In 1851 Alexander Ramsey wrote: “In tracing the origin of the Indian races around us, we should not overlook the necessity of preserving their languages, as most important guides in this interesting, though perhaps unavailing pursuit. It must be evident to all, that they are destined to pass away with the tribes who speak them, unless by vocabularies we promptly arrest their extinction.”

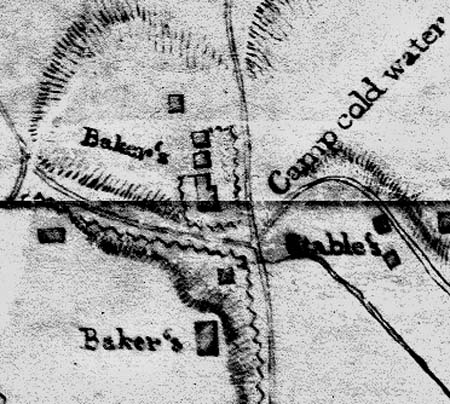

Alexander Ramsey and Henry H. Sibley, who helped engineer the 1851 treaties with the Dakota, and committed other acts worth detailed cataloging, or posthumous indictment, were both there when the Historical Society was founded in 1849. But if one wants to catalog the crimes of Ramsey and Sibley one needs to begin in the very records kept by the Minnesota Historical Society. People who commit crimes against humanity are sometimes proud of what they have done. The commitment to keeping a record of their actions sometimes blinds them to the understanding of what that record will show. Such records illuminate the nature of the acts but also the complexity of character that led to them.

In December 1850, Alexander Ramsey, as governor of Minnesota Territory, supervised a series of government actions that led to the deaths of hundreds of Ojibwe people at Sandy Lake. The full record of those actions is found in both the National Archives and the Minnesota Historical Society, recorded meticulously by government employees. Ramsey himself wrote in his diary that he could not believe the reports that Ojibwe people were dying in large numbers. On Christmas day he received a visit in St. Paul from the Sandy Lake Indian agent John Watrous, who knew very well what was happening, but, Ramsey reported, Watrous presented him with a “fine long sleeved pair of fur gloves,” and “a pretty segar case.”

A cheerful man, Ramsey was blind to the fatal irony of these gifts, as he was of so much in his life. He and his descendants kept his records carefully and finally gave them to the Minnesota Historical Society. Others who were equally or more guilty appear to have been aware of the nature of their actions, or at least their heirs were. In the case of Henry M. Rice, the same Minnesotan whose white marble statue is in the Statuary Hall of the U. S. Capitol in Washington, who masqueraded all his life as a “friend to the Indian” but dealt with them ruthlessly through a series of terrible treaties, his records were carefully purged of anything that told the true story of his acts.

Rice’s actions were not widely publicized at the time, but were understood by many. Jacob V. Brower, the archaeologist, credited with a pivotal role in the creation of Itasca State Park, deplored Rice’s role in the theft of the land of the Mille Lacs Ojibwe. Brower had no academic distance from the topic of his study. He had a clear understanding that archaeological record of the Mille Lacs area could not be separated from the treatment of the Indian people who still lived there.

In 1901 Brower addressed a meeting of the Minnesota Historical Society in which he “went to a considerable extent into early Indian history and condemned in the severest terms the persecution of the Indians by the government and the settlers.” He reportedly said that “if such wrongs continued the day would come when the destruction of the government would be chronicled.” (This is from a November 12, 1901 St. Paul Dispatch article.)

The address was a shock to some members of the Historical Society. General John Sanborn, a politician and the director of the Minnesota Historical Society at the time, described Brower’s address as “too radical in places and thought it might be softened a little before it became a record of the society.” Brower published the statement uncensored, at his own expense, but it soon became a valuable record in the Historical Society where one can find it when compiling the full record of Henry Rice’s life.

This incident describes both the strengths and weaknesses of the Minnesota Historical Society. While the Society tries to be comprehensive in its collecting of history, it is also wary, suspicious, conservative, and nervous about controversy. When it comes to interpreting history, the leadership of the Society usually places popularity above truth or complexity.

This is because of the nature of the role that the Society plays in Minnesota civic life. The Society occupies a sacred space in Minnesota, rather like the Vatican, which is why it is only fitting that the Society displayed the recent exhibit of Vatican treasures. The Society is an agency of the state without being a state agency. The Historical Society has the state archives and a free library. It operates a state historic sites network and is designated to receive a variety of federal funding on behalf of the state. The Minnesota legislature gives it many tasks to do, but the Society remains not part of state government. Instead it is perhaps the oldest 501(c)(3) in Minnesota.

In particular, the Historical Society is not a state agency in the strict legal sense of the term, as determined by a ruling from the Commissioner of Administration in 2006. For this anomalous reason, the Historical Society is not required to follow one of the most important laws regarding public record-keeping and the dissemination of information, the Minnesota Government Data Practices Act. That is to say, that the agency given the task of aiding and furthering public record-keeping in Minnesota and helping to carry out aspects of the Data Practices Act is not actually subject to the act. Instead the Society has its own seldom publicized information policy. This policy states that the society “may deny or limit access to information if providing access would harm the interests of the Society,” an enormous loophole that any state or local government agency would find very useful. Among other escape clauses, the policy states that the Society reserved “the right to amend or terminate this policy as it deems appropriate.” Until recently the exact words of this policy were unavailable to those seeking information from the Society, even when they were denied access to information in the possession of the Society.

Many will say that the role of the Historical Society as a non-state state institution—including not being subject to the Minnesota Government Data Practices Act–explains its strength, making possible its sacred functions as keeper of history in Minnesota. But the Society is still publicly funded to a large extent and is not insulated from any of the political pressures that engender a persistent fear of controversy, unlike the University of Minnesota. The university is expressly named in the law as subject to the Minnesota Data Practices Act and does not seemed harmed as a result. Perhaps the doctrine of academic freedom makes a difference.

To return to the starting point, it is precisely in situations in which the status of the Historical Society is at issue that a dominant master narrative so damaging to Indian people makes its appearance. Fear of the legislature increases the stereotypical and superficial presentation of history to the public. In the long run one might hope that adequate, even lavish funding would allow the Society to overcome this recurring syndrome, but sometimes the desire for funding becomes not a means to an end, but a never-ending quest. Circuses become more important than bread. Without a firm tradition of academic freedom to support it, the Society believes it can only hide behind its sacred status and a pious facade if it wishes to survive in the winds of Minnesota legislative politics.

More about master narratives and the Minnesota Historical Society next time

A Personal Note about My Conflict of Interest

Some will say that my credibility about the Minnesota Historical Society, pro or con, is simply nonexistent. My mother worked there for many years (though before her death in 2008 she was very critical of it). I worked there for ten years myself (and ever since then have been described as “disgruntled former staff”). And while working there I met my wife who still works there (which causes many interesting family arguments at the dinner table). On top of that the Historical Society published my book We Are at Home: Pictures of the Ojibwe People in 2007. I am sure there are some at the Historical Society who believe that I have been too harsh toward the institution. Others will say that I have been too easy. In fact both of these points of view may be right, depending on the occasion. I can give you examples of both. But it seems to me that I have an obligation to be as harsh or as easy toward the Historical Society as I have been in my writing toward the National Park Service, the Minnesota Indian Affairs Council, the Minnesota Department of Transportation, and the Office of the State Archaeologist. To act any differently is hypocritical. So, despite the complexity of my relationship with “the oldest 501 (c) (3) in the state,” I will try to muddle through, sorting out the issues as they arise.