Deadline for comment on the desecration of the Afton Effigy Mound is Thursday, September 1, 2016, at 4:30 PM (not midnight). Here’s the pdf that includes information on how to submit comments: www.pca.state.mn.us

Throughout the history of Minnesota as a European-American place there are many examples to demonstrate how Native sacred and culturally important sites should be acknowledged, preserved, and respected, and, conversely many examples of how such sites have been ignored, desecrated, and despised. These examples do not all fit the common stereotypes of who has protected sacred sites and who has not. While Native people have often fought for the protection of such sites, there are examples of individual Native people and tribes letting desecration happen, even collaborating in it, and there are other examples of Non-Native people seeking to carry out an enlightened and unexpected stewardship, something that could be a good example for other White people.

The mounds in St. Paul’s Indian Mounds Park have come to receive an increasing amount of protection and acknowledgement for their sacredness, after a period of initial desecration and neglect. It is not known if a similar degree of acknowledgement and protection will ever occur for the Afton Effigy Mound.

The mounds in St. Paul’s Indian Mounds Park have come to receive an increasing amount of protection and acknowledgement for their sacredness, after a period of initial desecration and neglect. It is not known if a similar degree of acknowledgement and protection will ever occur for the Afton Effigy Mound.

One unexpectedly enlightened White person lived in the town of Afton and did his best to show stewardship over the Afton Effigy Mound–the same mound that Afton seeks to desecrate–part of which lay in his own back yard. His name was D. J. Peabody. A 1956 Stillwater newspaper reported his story:

INDIAN GRAVE. D. J. Peabody of Afton steadfastly refuses to budge a 10-foot high Indian mound in his backyard. “I could use all that fill for the rest of my backyard, but I wouldn’t want anyone digging up my grave,” the 60-year-old retired mechanic says. He now runs a hobby shop next to his home.

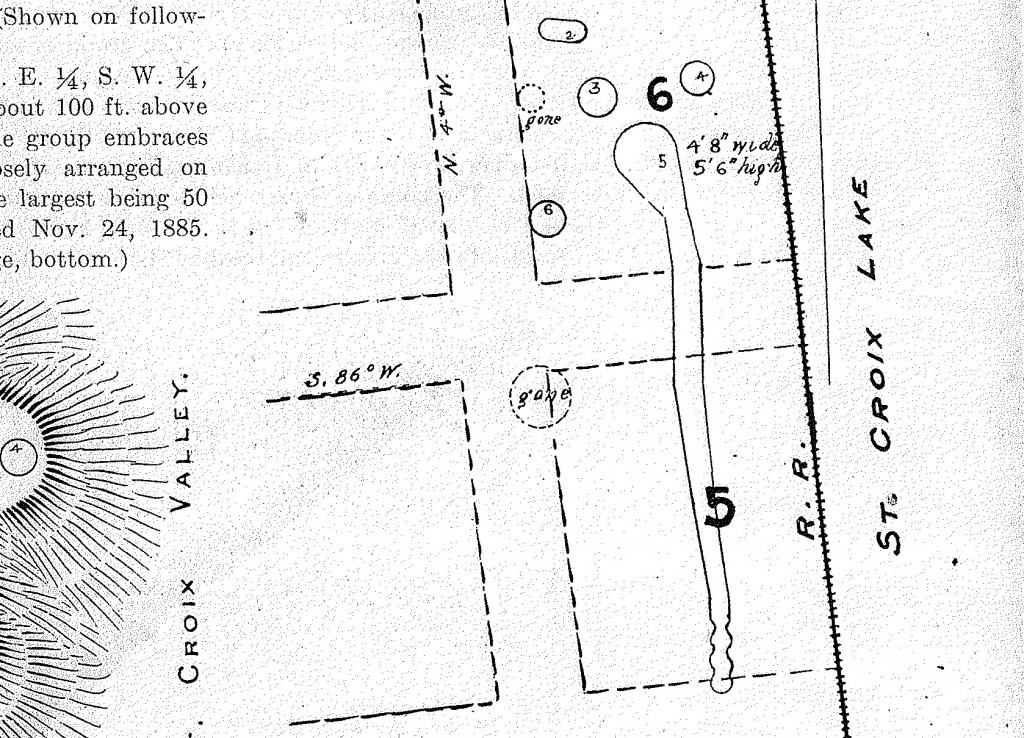

Both Peabody, who has lived in Afton since 1924, and his father-in-law Frank Squires, another long time resident firmly believe the mound was the head of a 150-foot-long fish-shaped Indian burial ground. Time, erosion, floods, and cloudbursts have wiped out its contours excepting the head.

At least one tomahawk and a number of arrowheads have been found in the mound, Peabody says. A number of years ago several workmen uncovered two skulls from the body of the fish.

Peabody is grading the mound slightly so that he can plant grass and keep it mowed.

“Sometimes I just like to stare at the mound and wonder how many Indians are buried there and how they died and and what kind of people they were.”

Given the way in which the Afton Effigy Mound began to be desecrated after Peabody died, and given what may happen with the sewage treatment facility advanced by the Minnesota Pollution Control Agency today, D.J. Peabody was clearly a rare and exceptional resident of Afton.

But Peabody was not the only White resident of Minnesota who sought to carry out an enlightened stewardship over Native sacred and culturally important sites. An early history of the town of Winona, Minnesota (History of Winona and Olmsted Counties, 276-277) tells the story of a “settler” named John Burns who came to live on a plot of land in a valley adjacent to the later town of Winona, having received permission to settle there from Wabasha’s band of Dakota, prior to their enforced removal to a reservation on the Upper Minnesota River in the 1850s, and their later exile from the state of Minnesota in 1862.

“The locality was the special home of Wabasha and his family relatives when living in this vicinity. It was sometimes called Wabasha’s garden by the old settlers.” The account states that this land contained a burial ground. The Dakota asked Burns to respect the burials which he did faithfully:

Quite a number of Indian graves were on these grounds. Nearly in front of the farmhouse there were two or three graves of more modern burial lying side by side. These were said to be the last resting-place of some of Wabasha’s relatives. The Sioux made a special request of Mr. Burns and his family that these graves should not be disturbed. This Mr. Burns promised, and the little mounds, covered with billets of wood, were never molested, although they were in his garden and not far from his house. For many years they remained as they were left by the Indians, until the wood by which they were covered rotted away entirely. A light frame or fence of poles put there by Mr. Burns always covered the locality during his lifetime.

One must also acknowledge the many more accounts of mounds leveled, destroyed and generally obliterated. It is no wonder that the Town of Afton now seeks to desecrate the Afton Effigy Mound. Rather than paying D.J. Peabody his due, following his example of good stewardship and that of John Burns in Winona, the now seeks to erect a highly visible evidence of the sorry legacy of White Minnesota as a place where sacred sites are not given the protection they ought to receive, where paradise is torn down to put up a parking lot. It is a shameful history. And now it will be Afton’s shame too.