“Minnesota–150 Years of Denial.” That was my motto proposal for Minnesota’s statehood centennial which began in May 2008. All through this year I’ve been thinking of Carol Bly. She died in December 2007, but if there was ever a time that needed her spirited involvement it was the year of Minnesota’s sesquicentennial—the uproar, the arguments, the anachronistic nostalgia, the covered wagons, and the Lincoln impersonators teaching children how to make stovepipe hats. All of this could have used her skills at making people who disagree sit down and talk.

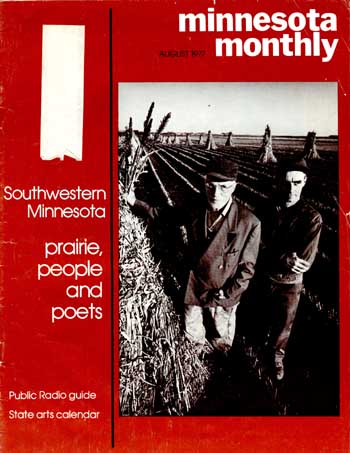

In the 1970s Carol Bly wrote a series of essays in the magazine of Minnesota Public Radio—first called Preview, then Minnesota Monthly—under the title that was later given to her book Letters from the Country. These letters explored the difficulties of sorting out questions of public culture and interpersonal communication in small towns and in the country. Carol Bly had a reforming spirit. She was not from the area of southwestern Minnesota where she and her husband the poet Robert Bly lived. Born in Duluth, she was educated at Wellesley, had lived in the east, and had gone to graduate school at the University of Minnesota before arriving in Madison, Minnesota.

Carol Bly always reminded me of the fictional Carol Kennicott in Sinclair Lewis’s Main Street, an outsider who took life in small towns seriously and wanted to make things better. Personally, when I was younger, I did not care for Carol Bly’s writing. But I was not a real Minnesotan and had never lived in a small town for very long so I did not really understand her work. My mother lived in a small town then and she had a grudge against Carol Bly, which was odd because they were two peas in a pod when it came to speaking up when speaking up was necessary. It is only recently that I have begun to see the profound value in Bly’s forthrightness (and in my mother’s for that matter).

Carol Bly’s letters were begun during the Vietnam War and were continued in its aftermath. Bly was insistent that even people in small towns should confront the nature of the what was going on in the world then, not back away from it. Bly had an unerring sense for spotting hypocrisy and the little evasions of everyday conversation. In this her work is the converse of Howard Mohr’s. What Mohr saw as humorous in how Minnesotans talked, Bly saw as tragic denial.

Bly’s letters are a Babette’s Feast of humanizing strategies for making people become better human beings, better listeners, better talkers, better sayers and doers of hard things. Of course, there is no question that Bly drove a lot of people crazy whether they lived near her or simply read her essays. She admitted in the new preface to the 1999 edition of her book that the first third of the letters were “a little cross,” with an edgy tone, and that the later essays were “directive and even more opinionated,” even though at the end she said she felt more sure of her subject “informally analyzing rural life and trying to figure out ways to live both more seriously and more happily than seemed to be the general custom.” Bly’s work speaks to a larger human condition, about how to confront things and change them. But it also describes the general public culture of this 32d state, this arbitrarily constructed place called Minnesota, the state that is now almost 151 years old.

What makes the Bly’s work even more remarkable is that it was published in Minnesota Monthly, which is now a slick advertising vehicle designed to raise money for public radio. But in those years the magazine was a far cry from what it is now. It had less advertising but it was a far better magazine. It started out as a monthly program guide but gradually turned into a stimulating and ground-breaking journal of opinion and analysis about Minnesota and its culture. One issue from August 1977 that I still have included an essay by Paul Gruchow entitled “Pieces of the Prairie,” illustrated with photographs by Jim Brandenburg, a piece by Bill Holm on “Icelanders, Box Elders, Soybeans and Poets,” along with Carol Bly’s letter from the country on the topic of facing evil. This was a vital magazine that helped to explain Minnesota to Minnesotans. It has left a great legacy, through the work of each of those writers who have now sadly left us and particularly in the work of Carol Bly.

So much of what Bly speaks about in Letters from the Country rings true for public discussions throughout Minnesota, not just in those small towns. There is an evasive quality to the way Minnesotans in general and in particular deal with problems and issues that they share in common. There is an avoidance of conflict and a desire to smooth things over before they’ve gotten out in the open.

In Minnesota when you complain about something that involves society and general but also affects you in particular, you are likely to get the response suggesting that your complaint was motivated by egotism. I think of Carol Bly every time I complain to someone about something I believe to be a public wrong. Often the response is something like: “Why take it personally? It’s not about you.” Often this is said as a consolation but at other times it is intended as crushing retort, as though it answered all objections. What does one have to do to try to change society here in Minnesota, file a class action lawsuit, to prove that you know it is not just about you?

Similarly when things are heating up at public meetings in Minnesota and a few people have gotten angry enough to actually express an opinion, someone is likely to try to look on the bright side of things and say: “Isn’t it nice we have so many opinions represented here?” You want to respond, “Actually, no, it’s not nice, it’s hell, but then that is the price you have to pay for talking about tough topics.”

The key problem in Minnesota is that a lot of times people don’t want to talk with people with whom they disagree. Someone will say something occasionally but often the response will be silence. The difficulty is to keep the conversation going until everyone has had a chance to have their say, air their views, find a few things to agree on, identify the real issues and then try to do something about it. Instead grudges will be formed that become a real obstacle to progress.

Carol Bly’s solution was described in an essay entitled “Enemy Evenings.” She wrote that in Minnesota towns “one sometimes has the feeling of moving among ghosts, because we don’t meet and talk to our local opponents on any question.” According to Bly people didn’t air their differences because it was a “hassle,” and people would get upset. The result, she said, was a dismal loneliness, exercised in hypocrisy. Bly’s solutions was the enemy evening, a phrase inspired by Nixon’s enemies list, where people who disagreed with each other on particular issues would come and present their differences as panels of speakers. The event would be moderated by “a firm master of ceremonies in whom general affection for human beings would be paramount, not a chill manner or a childish desire to get the fur flying.”

Bly wrote that rural Minnesotans needed more “serious occasions” and serious discussion, such as these enemy evenings. Minnesota manners were pleasant and friendly but at a price to individual Minnesotans:

To preserve our low-key manners they have had to bottle up social indignation, psychological curiosity, and intellectual doubt. Their banter and their observations about the weather are carapace developed over decades of inconsequential talk. [Take that Howard Mohr!]

She concluded the essay stating: “I commend frank panel evenings with opponents taking part: let’s try that for a change of air, after years of chill and evasive tact.”

A former non-Minnesotan like myself ought to point out that the phrase enemy evenings betrays a lot about Minnesota culture. It implies that if you disagree with someone here you may soon be classified as an enemy. But Bly’s strategy was to figure out how to make enemies into co-conversationalists. Elsewhere in her letters she proposed further ways of airing disagreements. For thing she noted that one evening was not enough to really cover these kinds of discussions. Overnight conferences were the solution, allowing people to meet casually during breaks, sleep over and meet again the next day, providing an opportunity for those with “out-of-control agendas” to get it out of their systems, and generally to allow people to “concert together,” as Tocqueville had put it, and “have a go at the ‘mutual awakening.’”

Much of Carol Bly’s insights in dealing with differences of opinion here offer lessons for the Minnesota sesquicentennial and its aftermath. There may be some who would condemn the work that Angela Waziyatawin has done over this sesquicentennial year, making use of all the evasions of Minnesota-Nice-speak. Her opposition to the idea of “celebrating” events that were tied to the goal of wiping out Native American communities in Minnesota, may have been viewed as evidence that Waziyatawin is taking things personally and believing it is all about her. Many would prefer to see her go away and stop complaining.

For example, it is interesting to note that the reports I’ve read so far about the open house at the VA Hospital on February 23, have said very little about Waziyatawin’s role at the event. A new article in the Southside Pride, does not mention that, at this open house she got up on a chair and spoke to those assembled at some length, followed by speeches of her supporters and other Dakota people. The response to what she said, it may appear, is silence. (Of course there are some who will point out that MinnesotaHistory.net has not yet said anything about the event in any detail either. That is a reasonable criticism. Why doesn’t somebody send me an account? I’ve been too busy to write it myself.)

One can certainly disagree with Waziyatawin’s manner of raising the issues that she raises or disagree about the solutions that she is seeking, but one should never make the mistake of believing that these are not serious issues and that after 150 years of silence they not should be ones of continuing discussion. Minnesota’s history matters because it continues to have an effect on people today. The evils of the past as well as the good have helped make Minnesota what it is now. Acknowledging the past is an important step to take.

Carol Bly wrote that it was worthwhile for a community to get together and discuss how we might praise those we admire, even if we disagreed on who to praise and how to praise them. She added: “We could do some condemnations too. I like a fight.” I’m with her there, especially about history. Let’s talk about our history here in Minnesota. Let’s get it all out. No one gets to tell anyone else to shut up. Let’s agree, let’s disagree, let’s agree to disagree and disagree to agree, but let’s keep talking. After 150 years, it’s time to end the denial.

This essay channels Carol Bly.

Enemy Evenings are called for.

Readers who believe Bly matters can hear her here:

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Sn2tHdANAt8

I adore Carol Bly’s writing, precisely because she was so forthright and was willing to pick a fight. She believed that even fiction could be a vehicle for discussing the larger tough issues. I take her advice to heart in my own writing.

In adding to your points about Minnesotans wanting to avoid conflict, have you ever heard of “the meeting after the meeting”? For those not familiar with the term, what we often see in Minnesota is that meetings will be held, but no one will discuss what they are really thinking. The meeting will end and everyone will have been nice to each other, but nothing important will have been decided. After the meeting, some people will leave, but others will group up and finally talk about what should have been discussed during the meeting. We need to live by Carol’s example in order to overcome this behavior.

On a personal note, I had exchanged a few emails with Carol before her untimely passing and I regret that I never had a chance to meet her.

A friend of mine read this and sent me an email. He said:

It is not just “Minnesota Nice,” it is also “Midwestern Nice.” Even though I’m from Wisconsin, I very much see myself in the description of people who prefer silence to talking things out, especially in recent political “conversations” with my mother. Politics was never discussed in my home when I was growing up, and I did not benefit from the training around the supper table, arguing with my family. Now that my mom is a little more vocal, I’m ill-equipped to respond. Heavens: I couldn’t possibly suggest that she’s mistaken in certain beliefs. Once, when I had to set her straight by e-mail (she’d forwarded some insane Internet rumors), I endured the classic “fight or flight” symptoms but persevered. Baby steps, I guess.

Thank you for expressing what I have felt and thought about Carol, Wi!!! even worse state for such clarity. I try to live as Carol wished,she was pure truth, which takes wisdom to understand her words..back in St.Paul,things have not changed since I grew up here 58 yrs ago! Same fight…